If you have the chance, on a sunny morning, to contemplate the medieval towers of Maastricht from Mount Saint Pieter, you will not find it hard to imagine yourself back in centuries past. Strolling down the hill towards the city, you might pass along cornfields, stroke a horse’s head over the barbed wire and pick a poppy flower from the grass. Your steps slowly lead you towards Aldenhof park, at the gates of Maastricht…

If you have the chance, on a sunny morning, to contemplate the medieval towers of Maastricht from Mount Saint Pieter, you will not find it hard to imagine yourself back in centuries past. Strolling down the hill towards the city, you might pass along cornfields, stroke a horse’s head over the barbed wire and pick a poppy flower from the grass. Your steps slowly lead you towards Aldenhof park, at the gates of Maastricht…

But suddenly a tall cast iron statue reminds you that this place was not always so quiet and peaceful. Indeed, in ancient turbulent times, these very spots once resonated with the thunderous clamour of weapons. The statue portrays the glorious musketeer Charles de Batz-Castelmore, better known as d’Artagnan, who perished in 1673 during the siege of Maastricht by the armies of the French king Louis XIV.

Un pour tous, tous pour un, read the chiselled letters on the socle – One for all, all for one. The bold eyes of the musketeer, who is drawing his sword, speak of firmness. The statue is a tribute to a noble man’s courage and contempt of death as he remained true to his king and comrades.

Un pour tous, tous pour un, read the chiselled letters on the socle – One for all, all for one. The bold eyes of the musketeer, who is drawing his sword, speak of firmness. The statue is a tribute to a noble man’s courage and contempt of death as he remained true to his king and comrades.

The myth of d’Artagnan

The name of d’Artagnan acquired world fame thanks to the 19th century novels of the flamboyant French writer Alexandre Dumas, who in a matchless style described the gallant conversations and splendid sword fights of his hero. The D’Artagnan romances, which comprise The Three Musketeers and its sequels Vingt ans après and Le Vicomte de Bragelonne celebrate the martial exploits of the French king’s elite troops in gripping merry ventures.

Dumas found the basis for his characters in a novel published in 1701 by a certain Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras. Dumas’ stories, on their turn, were a source of inspiration for countless other books, plays and films about d’Artagnan and his fellow musketeers Athos, Porthos and Aramis.

But d’Artagnan is not just a myth. In France, schoolchildren learn how the illustrious Lieutenant-Captain of the king’s musketeers was killed before the ramparts of Maastricht. Dumas’ famous three other musketeers truly existed too.

The reality of war

Yet, even though it successfully stirs interest, the romantic genre which brought so much success to Dumas is not suited to reproduce a correct picture of history.

Indeed, the d’Artagnan romances do not report on the violent reality of war, with its aftermath of plagues and misery. They do not ponder much on the injustice that fell upon poor local peasants when passing armies would lay them under contribution, or when rough soldiers would quarter in their villages and tear down their humble dwellings if these happened to be standing in the line of fire.

Indeed, the d’Artagnan romances do not report on the violent reality of war, with its aftermath of plagues and misery. They do not ponder much on the injustice that fell upon poor local peasants when passing armies would lay them under contribution, or when rough soldiers would quarter in their villages and tear down their humble dwellings if these happened to be standing in the line of fire.

Nor did Dumas describe the fate of the besieged citizens of Maastricht, who were forced to help dig trenches, suffered of starvation and were killed by cannon balls flying about. No word either about the beastly rage of mercenaries, to whose merciless hands a city would sometimes be abandoned if it surrendered only after a long siege.

But why should indeed Dumas have written about the miseries of war? His primary intention was after all to tell stories in which readers would dream away…

Who was the real d’Artagnan?

Charles de Batz-Castelmore, Count d’Artagnan, was born in 1610 or 1611 in the castle of Castelmore in Lupiac, in the French province of Gascogne. In 1627, like many young noblemen, he travelled to the court of Louis XIII in Paris. There he became commander of the ‘grey’ musketeers, named after the colour of their horses. In fact, they were the king’s lifeguards, and accompanied him everywhere. D’Artagnan accomplished delicate tasks at the service of the crown: he escorted important prisoners and carried secret messages. He married in 1659, fathered two sons, but divorced a few years later. In 1672, he became governor of the Flemish city of Lille, which had come under French rule only a few years earlier. Here, too, he had to act with tact and authority.

Charles de Batz-Castelmore, Count d’Artagnan, was born in 1610 or 1611 in the castle of Castelmore in Lupiac, in the French province of Gascogne. In 1627, like many young noblemen, he travelled to the court of Louis XIII in Paris. There he became commander of the ‘grey’ musketeers, named after the colour of their horses. In fact, they were the king’s lifeguards, and accompanied him everywhere. D’Artagnan accomplished delicate tasks at the service of the crown: he escorted important prisoners and carried secret messages. He married in 1659, fathered two sons, but divorced a few years later. In 1672, he became governor of the Flemish city of Lille, which had come under French rule only a few years earlier. Here, too, he had to act with tact and authority.

The young republic

In 1632, the Dutch prince Frederik Hendrik of Orange had conquered the fortified city of Maastricht from the catholic Spanish Habsburg king. From that moment on, the city served as an outpost in the hands of the protestant Republic of the United Provinces of the Netherlands.

The young republic entered its golden age. Ship owners from Amsterdam sent their vessels around the world and rapidly acquired enormous riches. Holland became a refuge for Huguenots and free thinkers of all kinds, and a centre of art and science. Established powers like England and France saw this bloom with a mixture of envy and disdain, and tried in turns to deflate the daring Dutchmen. But this was no easy task.

The young republic entered its golden age. Ship owners from Amsterdam sent their vessels around the world and rapidly acquired enormous riches. Holland became a refuge for Huguenots and free thinkers of all kinds, and a centre of art and science. Established powers like England and France saw this bloom with a mixture of envy and disdain, and tried in turns to deflate the daring Dutchmen. But this was no easy task.

During two sea wars against England, the fleet of the admirals Tromp and de Ruyter remained intact with remarkable skillfulness. But in 1672, the ‘year of disaster’, the situation became threatening: there was much discord in Holland about the princes of Orange, whose prominent position did not seem to fit a republic. Now England, France, Münster and Cologne all at once turned against the United Provinces of the Netherlands.

The Sun King

In those years, the French Sun King Louis XIV was building his baroque palace in Versailles. He was the soul of the alliance against Holland. Yonder in that small country of frogs by the sea, those princes of Orange were thinking a great deal of themselves, weren’t they? But had they been anointed kings like himself, his very Christian majesty by the grace of God? Didn’t his marriage with the Spanish infante Maria Theresa give him more rights to lay claims on the Spanish northern hereditary lands? The Dutch were just peasants. A country without a king was not a real country. Even France’s existence depended on its king. “L’Etat, c’est moi”, declared Louis XIV.

In those years, the French Sun King Louis XIV was building his baroque palace in Versailles. He was the soul of the alliance against Holland. Yonder in that small country of frogs by the sea, those princes of Orange were thinking a great deal of themselves, weren’t they? But had they been anointed kings like himself, his very Christian majesty by the grace of God? Didn’t his marriage with the Spanish infante Maria Theresa give him more rights to lay claims on the Spanish northern hereditary lands? The Dutch were just peasants. A country without a king was not a real country. Even France’s existence depended on its king. “L’Etat, c’est moi”, declared Louis XIV.

The Sun King believed that the French speaking regions of Alsace and Wallonia belonged to France’s natural territory. He wished to shift the country’s frontiers to the Rhine river. So he declared war on Holland.

Around this time, the famous poet Jean de la Fontaine wrote a political fable for his monarch, in which he portrayed ungrateful frogs (the Dutch) rising in revolt against the Sun (the French King), who was warming them. In the final lines of Le Soleil et les Grenouilles, the frogs are warned to beware against provoking the sun’s wrath:

Car si le soleil se pique,

Il le leur fera sentir ;

La république aquatique

Pourrait bien s’en repentir.

(For, should the sun in anger rise,

And hurl his vengeance from the skies,

That kingless, half-aquatic crew

Their impudence would sorely rue.)

But there was however one problem for the French: to reach the Rhine, Louis XIV had to conquer Maastricht. And Maastricht was one of the strongest fortified cities of Europe.

The siege of Maastricht

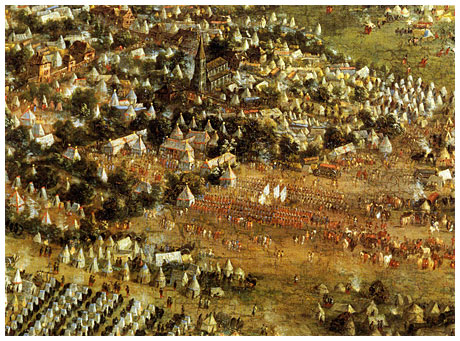

The thirty-four year old Sun King took personal command over the siege of Maastricht. He pitched his tents on the Louwberg hill, next to the church of Wolder. His renowned fortifications engineer Vauban organised the technical aspects of the siege, such as the construction of provisional circumvallations to avert any relief force, and trenches of approach towards the city. Their English allies were under the guidance of the duke of Monmouth, a natural son of King Charles II.

The thirty-four year old Sun King took personal command over the siege of Maastricht. He pitched his tents on the Louwberg hill, next to the church of Wolder. His renowned fortifications engineer Vauban organised the technical aspects of the siege, such as the construction of provisional circumvallations to avert any relief force, and trenches of approach towards the city. Their English allies were under the guidance of the duke of Monmouth, a natural son of King Charles II.

D’Artagnan was Lieutenant Captain of the first company of the King’s musketeers. He was to concentrate his troops’ assault on the Tongerse gate (Tongersepoort).

In 1673, the fortress of Sint Pieter, the High and Low Fronts and the Waldeck bastion did not exist yet. But the walls around the city had already been provided with large outworks. To the north of the Tongerse gate for instance, stood a seventy metre long and forty metre wide earthen hornwork, perpendicular to the wall and supplied with a hiding place made of stone. Before the gate, among other fortifications, the Dutch had built a brick covered lunette, which later became known as the ‘demi-lune des mousquetaires’. To the south, stood yet another lunette, next to the De Reek watergate, where the Jeker streams into the city. The city had also been provided with underground passages which helped the besieged garrison identify and undermine the trenches of approach.

The attack

On the night of Saturday 24 to Sunday 25 of June, 1673, the French army captured the advanced lunette before the Tongerse gate. On Sunday morning, however, the Dutch garrison reconquered it with the use of explosives. The young and unthinking duke of Monmouth now persuaded the sixty-two year old d’Artagnan to take part in a counter attack without sufficient cover.

On the night of Saturday 24 to Sunday 25 of June, 1673, the French army captured the advanced lunette before the Tongerse gate. On Sunday morning, however, the Dutch garrison reconquered it with the use of explosives. The young and unthinking duke of Monmouth now persuaded the sixty-two year old d’Artagnan to take part in a counter attack without sufficient cover.

The musketeer had hardly recovered from the battle of the previous night. As he passed a bottleneck, he was hit in the throat by a musket bullet. D’Artagnan fell and succumbed to the fatal wound.

The duke stepped across his corpse and recaptured the lunette. Within a few days, the French army was able to make a breach in the city wall. The siege of Maastricht had lasted only thirteen days when the city surrendered on June 30, 1673.

D’Artagnan had been loved not only by his fellow musketeers, but also by the king himself. On the evening of that fateful Sunday, Louis XIV wrote in a letter to his wife: “Madame, today I lost d’Artagnan, in whom I had every confidence”.

After the capture of Maastricht, Louis XIV ordered a triumphal arc to be erected in Paris to celebrate this glorious feat of arms: a sculpture on the Porte Saint Denis represents an allegory of the surrender of the Dutch stronghold.

The King further immortalised the siege of Maastricht in paintings, struck medals and built a scale model of the city of Maastricht and its surroundings.

But the glory of war turned out to be transient: Sic transit gloria mundi. Within five years after the conquest of Maastricht, Louis XIV was forced to relinquish the city again, as a concession to the Dutch stadtholder, prince William III of Orange, who married Mary Stuart in 1677 and later on became king of England.