Cathedral-fatigue. Many visitors to Western Europe know the feeling all too well. The Duomo in Florence, Notre Dame de Paris, the Kölner Dom, St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome – the list goes on and on and is itself impressive, even if not exhaustive. Luckily for the afflicted, a refreshing surprise awaits those who head to lovely Maastricht.

Selexyz Dominicanen stands tall in the center of the city. A 13th century gothic church, it offers its visitors a breathtaking high ceiling, a majestic nave, grand ornamentation, and an opportunity to worship: not at the great altar of God, but at the many altars of literature.

Recently rated the world’s “fairest bookshop” by the UK’s highly-regarded Guardian newspaper, the Dominicanen has quickly become one of Maastricht’s tourist attractions. “After the Guardian article, this place has been a madhouse,” remarks William Remmers, General Department Head of the store.

Remmers recently met with a certain Crossroads reporter to answer a few questions about the church, the bookstore, and their shared history. We sat in what was once the sanctuary of the church, and where now buzzes a Coffeelovers café. “You have to mention Coffeelovers,” he insists. “They are a small Maastricht-based coffee store that sells pretty much the best coffee in the world.”

Remmers recently met with a certain Crossroads reporter to answer a few questions about the church, the bookstore, and their shared history. We sat in what was once the sanctuary of the church, and where now buzzes a Coffeelovers café. “You have to mention Coffeelovers,” he insists. “They are a small Maastricht-based coffee store that sells pretty much the best coffee in the world.”

The bookstore fits almost snugly between Maastricht’s two dominant squares, the Markt and the Vrijthof. The renovation project was led by Selexyz, a large Dutch bookstore chain, in collaboration with the city council of Maastricht.

Selexyz Dominicanen opened, to some medieval fanfare in November 2006. It was a joint development project with the adjacent and also recently-renovated Entre Deux shopping center. “Entre Deux,” which means between two in French, represents the site’s location between the two squares.

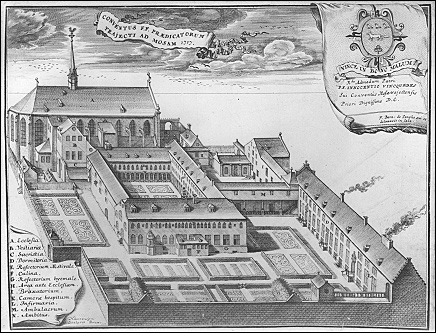

The Dominican friars began building their church in 1267, and it was consecrated in 1294. It endured through Maastricht’s often turbulent religious history for exactly five centuries until, in 1794, post-revolutionary French forces annexed the city and expelled the Dominicans. The French used the church for religious purposes for a little over a decade and then converted it to a warehouse.

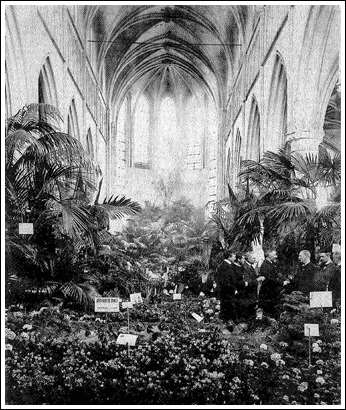

“[The French] cavalry used it for their horses. Since then, it hasn’t really been used as a church,” notes Remmers. “It’s been multiple things: bicycle storage; a place to take exams for classes; there have been boxing matches here; reptile and amphibian shows; Christmas markets; it was even used as a second-hand book salespoint. It hasn’t been a church for over 200 years.”

If its use as a bike storage and Christmas market do not feel shocking or Dutch enough, Remmers reveals that “during some periods, it was used as a place for Carnaval parties! A lot of people who come here say that they have been here when they were really drunk or that they met their wives here. They drank beer, partied, and did whatever people do during Carnaval.”

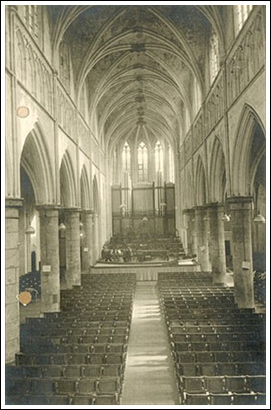

Emile Ramakers, library historian at the Centre Ceramique and co-author of Dominicanen: geschiedenis van kerk en klooster in Maastricht (trans. The Dominican: history of the church and monastery in Maastricht), explains: “The church was restored around 1910, and then it was no longer a storage room. It was a big empty space with a flat floor in the center of the city: a perfect place for festivities. They installed an organ and used it as a music hall. It’s also true that students from the nearby school [which was in the space now occupied by the Entre Deux shopping center] used it to take exams. And from the 50s up until the late 90s, it was also used for Carnaval.”

A foreign visitor might wonder if such odd reclassifications provoke a backlash from the Dutch public. “I think the bookstore is beautiful, and it has really become an attraction in its own right for Maastricht,” says Metka Hercog, a Ph.D. student in the Maastricht Graduate School of Governance. “But I do think that there are certain things that would not work well in a former religious space such as a church. There is a line that should not be crossed.”

It seems that the Dutch have a recent history of approaching this line, but most feel that they do not cross it. The Selexyz bookstore is not alone as a secular institution housed in a converted church. Maastricht’s own Kruisherenhotel offers visitors luxury accommodations in the architecture of a former monastery. Furthermore, there are churches in Rotterdam and Nijmegen that have been transformed into housing projects by the city councils.

“In the last few years, religion [in the Netherlands] is declining, and a lot of churches are abandoned. People still think that they should serve a decent purpose. Of course, there are always some things you can do with a church and some things you can’t do. If you wanted to sell erotic products here, I think most people would protest,” Remmers reflects, “although I never heard people complaining about this being a bicycle storage or a place to party during Carnaval.”

Still, Selexyz Dominicanen represents the first project in the Netherlands to turn a church into a bookstore. And, in fact, this conversion has been beneficial to the cultural heritage of the site.

The project team has conducted considerable restoration on the ceiling paintings: “One of the things we had to do was to clean them up,” says Remmers. “What you can see now is what could be rescued, so to speak. Before, you couldn’t even tell there was a fresco. People worked on the ceiling for months – I think it was a year – to clean it up as it is now.”

One indication of the great care with which the renovation was undertaken is perhaps the time the project took. Selexyz made its proposal in 2002, and worked with the city council of Maastricht and Entre Deux for the next four years before its opening in 2006.

This care is furthermore illustrated by the architectural design of the site: “You have to consider a lot of things,” says Remmers. “First of all, it’s a church. Second of all, it’s also a monument. So you have to treat it with care. Everything you see here stands alone in the room. It doesn’t come attached to the walls. The cabinets where we hold our books all stand aside from the walls.”

The site itself asserted its monument status when, during renovation, a small bone was found just under the floor. “And when you find a bone, someone says, ‘this has some archeological significance, and we need to study this further.’ So they rip open the entire floor and they dig out everything they can find. Because, of course, this is a church and people were buried here. You can still see the gravestones lining the floor. And they have to know who it was and catalogue every little bone they find. And after that, they just dump it back, and you can finally put in the floor.” Remmers adds, “That slowed us down a couple months.”

And restoration is ongoing. Atelier Limburg is currently working on a mural on the northern wall. Ramakers notes that it is an exciting and extremely significant project: “The whole thing is very large: about seven meters high. More importantly, the mural is dated 1337 and is believed to be the earliest depiction of Thomas Aquinas.”

The Selexyz Dominicanen also hosts a variety of cultural events in its impressive space. For its 2006 opening, popular Dutch performer Herman van Veen did a show for about 300 people. More recently, on 13 January 2008, local artist Mine Stemkens gave a multimedia poetry presentation, with over a dozen people reciting her poetry accompanied by a cellist and performance lighting. Curtains from the event, with textual excerpts, continued to hang throughout the bottom floor of the bookstore for weeks thereafter.

The bookstore has generated much buzz in the online world. Crossroads’ photo feature on the opening of the store from the autumn of 2006 remains its most-viewed page. In addition, an Internet search reveals that there is also a good deal of interest from Japan. Remmers witnesses the manifestation of this popularity, noting, “[Japanese tourists] come in busloads in April and May. And they all go to the children’s section; they all want to take a picture with “Nijntje” [the popular Dick Bruna cartoon character also known as Miffy],” adding that Selexyz has not made any deliberate attempts to publicize in Japan.

A concern about the environmental effect of heating such a large space was also raised through a comment on Crossroads. Addressing this issue, Remmers is reassuring: “You may be surprised to learn that we don’t actually heat up the place. The only heating we have is in the floor, but that’s only minimal. It’s not like we’re trying to keep it warm here. During our busiest moments, there may be four-to-five hundred people walking here. So, that is also a lot of heat. Of course, there’s machinery running and lights burning, but there’s not some huge heat source that we use to heat the place. In fact, during the summer, we had a problem that it was too warm here.”

One of the reasons for this phenomenon is that the building is partly made of marl, a clay-based material that absorbs heat. “It’s very funny to see that when people arrive here in the summer, they think: it’s a church; it’s probably quite cool,” muses Remmers. “But it’s not; it’s actually rather warm.”

Asked about the Dutch reading habits, Remmers explains, “I think that the Dutch people like to read very much; they’re very versatile in their reading. The crime novels are very popular.” He adds, “Our English section sells very well. I think it has to do with a lot of people coming from Maastricht University who tend to read a little more in English.”

The Dutch, the students, and the expatriates certainly constitute a unique and vibrant reading culture in Maastricht. Appropriately, they all now have an equally splendid place to congregate.

By Amrit Dhir

Amrit Dhir is pursuing a masters in Media Culture at Maastricht University’s Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. Originally from Los Angeles, he received his bachelors degree in International Studies from Emory University in Atlanta.

Related article: Selexyz Dominicanen opens in Maastricht, November 2006

Acknowledgment: The black and white photographs have been reproduced from Dominicanen: geschiedenis van kerk en klooster in Maastricht (trans. The Dominican: history of the church and monastery in Maastricht), with the kind permission of Emile Ramakers, library historian at Maastricht’s Centre Ceramique and co-author of the book.

For more information about the Dominican Church and its renovation, visit www.heemschut.nl and www.monumenten.nl (in Dutch only)