In the 18th century, while most of Europe was shaking off centuries of superstition and beginning to prepare for the age of reason, the lands which now form the Dutch and Belgian regions of Limburg were terrorised by hordes of flying devil worshippers.

These mysterious robber bands met in caves or at isolated roadside chapels. Riding through the nightly sky on the backs of big black goats, they plundered farms and churches.

The ‘Bokkenrijders’, or ‘Goatriders’, owned the night throughout most of the 18th century, until they were finally brought to justice by brave and god-fearing officers of the law. This is a story that practically everyone in Limburg knows to this very day.

The Goatriders’ crimes

The story of the Goatriders is quite unique in the annals of crime. Not in the least because historians can’t yet agree on what exactly happened.

Hidden beneath two centuries worth of folklore and speculation some facts nevertheless emerge. The robberies and thefts attributed to the Goatriders certainly took place, as a visit to the historical archives in Maastricht easily can prove.

Also, between 1741 and 1794, a great number of locals were executed in present day Dutch and Belgian Limburg, accused of being members of these robber bands.

Transcripts of interrogations have survived in which suspects actually confessed to committing acts of sacrilege in churches and flying on the backs of goats, aided by the devil.

But the history of the Goatriders is really about the interpretation of historical events. We can’t take these simple, yet deceptive facts at face value.

As far as historians can tell, it all began with a string of small burglaries in the area around Kerkrade in 1741. When these crimes, which coincided with a surge in the number of wandering vagabonds in the area, were followed by a series of increasingly violent attacks on farms, as well as thefts from churches, local authorities came under a lot of pressure.

Unable to lay hands on the vagabonds, who disappeared into neighbouring lands after committing their crimes, they focused their attention on the local unwanted elements of society: the poorest inhabitants of Limburg, who often had to steal food or firewood to survive.

Arrests were made following a burglary in 1741 and the authorities of Kerkrade tried to blame all the unsolved robberies on these prisoners.

Necessary confessions were obtained through various instruments of torture, which were first applied with a certain degree of caution, according to the laws of the time, but later with diminishing restraint.

More and more prisoners, succumbing to the pain and the relentless questioning of their accusers, started ‘confessing’. Too often they were pressed until they would call out names, most likely of innocent relatives, friends, neighbours. Prisoners would later often withdraw these ‘confessions’, but to no avail.

The number of prisoners grew rapidly, filling dungeons well over their capacity. The authorities, in the mistaken belief that they were dealing with an enormous widespread robber band, started panicking and began intensifying their persecution of the ‘godless’ criminals.

Mass executions

Most of the prisons where the Goatriders were locked up can still be visited today. Castles like the ones in Herzogenrath and Hoensbroek, the cellars in the basement of Maastrichts’s Tourist Information Centre, the prison tower next to the Saint Pancras church in Heerlen and the museum on Valkenburg’s Grotestraat (where a plaque commemorating the Goatriders’ trials can be found today)… all these places, and many more, were crammed with prisoners.

Devoid of hope or any rights to legal counsel, the accused awaited the tragic ending that was in store for them.

When the public executions began, widows and children were cast out into the streets with empty hands, and the houses and all the possessions of the condemned were auctioned off to the benefit of their judges. Those who died in prison, or took their own lives, were hanged upside down from the gallows before being unceremoniously buried in the ground underneath.

The executions soon became widespread and many fled in fear of being accused. More and more people however began to notice strange inconsistencies.

Condemned prisoners screamed out their innocence at the crowds before being silenced forever. Victims of robberies often reported being assailed by small groups of four or five men, which didn’t stop the authorities from hanging between 40 or 50 men and women for that same crime. The amount of money the ‘robbers’ gained from their robberies, according to their confessions, often far exceeded the amounts actually lost by the victims.

In hindsight it’s easy to see these inconsistencies as a result of the unreliable methods by which the confessions were obtained.

If one thing is clear about the Goatriders, it is the fact that a great number of people must have met violent, degrading deaths while being completely innocent of any crime. Indeed it is quite likely that the Goatriders’ bands as such never even existed outside of the human imagination.

Flying goats

In several cases the brutality of the tortures inflicted upon prisoners, as well as the righteous indignation of over-zealous interrogators, mirrored those witnessed during the European witch trials of earlier centuries.

So maybe it’s not surprising to find out that a number of prisoners who were pressed too hard started making strange, hallucinatory confessions that bore uncanny resemblances to various types of folktales about witches.

Confessions about nocturnal meetings and the taking of sacrilegious oaths at roadside chapels, in which the robbers gave their souls to the devil, were of the greatest interest to the authorities who would then defend their brutal actions by claiming that the prisoners had sworn to secrecy. The ‘Goatriders’ oath’ became a standard subject during the interrogations and sometimes led to strange confessions about flying around the nightly sky on the backs of goats.

Even in those days the writing of the Goatriders’ history was a pick-and-choose affair, and the authorities stopped short of taking the flying aspect seriously.

These confessions did, however, cause enough of a stir among the public to have a lasting impact on the folklore of Limburg.

Starting around 1773 the word ‘Bokkenrijders’ (Goatriders) started popping up in several written sources describing the trials.

The executions came to an end when the ground of Dutch Limburg was saturated with blood and the horror had just become too great, leaving only bereaved and homeless families and nameless bones in the ground underneath the gallows.

The word ‘Bokkenrijders’ made its way to Belgium in 1773, where the trials flared up even more violently and a great number of people died at the hands of puritanical judges like the notorious drossaard Clercx from Overpelt.

Stigma

In the end about 450 people died as a result of the Goatriders’ trials, more than the approximately 120 people executed during the witch trials in Limburg, which took place during the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

But the nightmare didn’t end there.

The public executions had been designed as grisly spectacles that were meant to disgrace not only the condemned, but their families as well.

These measures proved somewhat more effective than the authorities may have intended, because small communities have very long memories. In fact, for the past 200 years being a descendant of an executed ‘Goatrider’ was the most unfortunate stigma that could be attached to an inhabitant of Limburg.

A contributing element was the fact that status changed very little in the course of time in the villages of Limburg. High positions were passed on from father to son for many generations, while the families who were poor in the 18th century remained so in the following centuries.

‘Goatriderblood’ was a derogatory term by which many a disreputable family was put into its place. Unsurprisingly, many historical records relating to the Goatriders have gone missing because of desperate people trying to clean their family history.

The first books that were written about the Goatriders didn’t improve the situation. In the 19th century the partially remembered historical events and oft repeated folk tales provided some local writers with material for romantic novels.

For a while there was a bit of a Goatrider renaissance in Limburg. Potboilers with increasingly implausible, highly melodramatic plots were churned out, aimed at barely literate working class readers.

The Goatriders became more evil than ever; portrayed as devil worshippers who practised obscene rites in the caves around Valkenburg and terrorised the countryside. These highly dramatic stories, such as De Bokkenryders in het Land van Valkenberg (1845) by Pieter Ecrevisse, Het Valkennest (1876) by Lodewijk Janssens and De geheimzinnige dokter-Rooverhoofdman (1869) by Adolf Mützelburg, set in the romantic landscape of Limburg, delighted the first tourists, who were shown all sorts of sites more or less associated with the Goatriders.

Some of these, like the popular hermitage at the top of the Schaelsberg near Valkenburg or the dungeon of castle Hoensbroek, did feature prominently in the Goatriders’ history, either as sites that were robbed or as prisons, while for others, like the caves of Valkenburg, the connection is somewhat more dubious. In fact, it’s likely that the association of these robber bands with the marlstone caves, where they are immortalised in at least two wall paintings, didn’t begin until the late 19th century.

Several local amateur historians, like Juliaan Melchior, a Belgian school inspector, and Henry Pijls, the mayor of Schinnen in Dutch Limburg, were disturbed by these developments and tried to set the record straight by writing serious books about the Goatriders’ history. But these writers were the literate inhabitants of the villages – priests, mayors and descendants of judges – who infused their works with local prejudice.

Goatriders remained evil fiends and their relatives infamous, which is why these writers were careful not to reveal full surnames in their books, preferring to use initials until the early 1970s, even though their readers knew very well, through village traditions, who they were writing about.

It took the enormous impact of World War II to upset the old ways enough for the Goatrider stigma to finally start dying off.

Revolution and rehabilitation

In some cases the fanatical way in which Goatriders were interrogated was obviously inspired by a growing fear among the higher classes of revolutionary tendencies among the populace.

The storm that was to become the French Revolution was no more than a dim shadow on the historical horizon at the time that the Goatriders were being executed, but nevertheless there already existed all over Europe secret societies who, inspired by the works of the writers of the Enlightenment, were dreaming of better days to come.

And indeed, we find in some documents statements from prisoners describing utopian fantasies of a better world that would come into being through violent means. It is partly because of these intriguing remarks that all restraints on the use of torture were sacrificed, with disastrous results.

After World War II several researchers started focusing on these particular confessions, offering a new interpretation of events. Apparently there was more to the Goatriders’ story than met the eye. Writers like Bernard Bekman and Ton van Reen penned successful novels in which the Goatriders were an early revolutionary band that was practising for the upcoming revolution by sacking farms. They were led by the mysterious physician Joseph Kirchhoffs, who was executed in Herzogenrath in 1772.

This theory, and the heroic robbers’ swashbuckling adventures, did much to rehabilitate the descendants of the executed, and today many a Limburger is proud to say he’s a descendant of a Goatrider! After all: didn’t the robbers band steal from the rich to feed the poor?

Today, the tragic events of the 18th century resonate in the landscape of Limburg and the collective memory of its inhabitants as harmless folklore. In places like Schaesberg, Heerlerheide and Herzogenrath we can spot statues of masked and cloaked picaresque figures seated on the backs of goats.

Though not very popular with the tourist board, the Goatriders are immortalised all over Limburg. Café signs, street names, a well in the Castle gardens (Kasteeltuin) in Oud Valkenburg… One can even follow a bicycle route devoted to their history.

Whether innocent victims of fanatical judges, organised criminals or early revolutionary bands, the Goatriders are inextricably linked with the history and identity of the Limburger. No longer associated with shame or superstition, they are now the symbol of the free willed inhabitants of Limburg and have become, in spite of what historians may have to say about it, the region’s very own Robin Hoods.

By Reggie Naus

Reggie Naus is a Dutch writer/freelance journalist with a special interest in folktales and history. He is the author of the book ‘De Vliegende Hollander: Biografie van een spookschip,’ which explores the legend of the ghost ship ‘The Flying Dutchman’. He has also written a study of a legendary 17th century robber in ‘Zwartmakerij in het Land van Ravenstein’. He is currently working on his first novel. His website can be found at www.reggienaus.com .

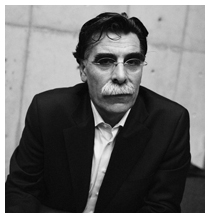

In the interviews he’s given to the media, the Iranian born writer Kader Abdolah says that he hopes that his books will lead to a better understanding of Islam and help promote the dialogue between Muslims and non-Muslims.

In the interviews he’s given to the media, the Iranian born writer Kader Abdolah says that he hopes that his books will lead to a better understanding of Islam and help promote the dialogue between Muslims and non-Muslims.

Whether it’s their first or last question, there is one thing my American friends always ask about my life here in the Netherlands.

Whether it’s their first or last question, there is one thing my American friends always ask about my life here in the Netherlands.

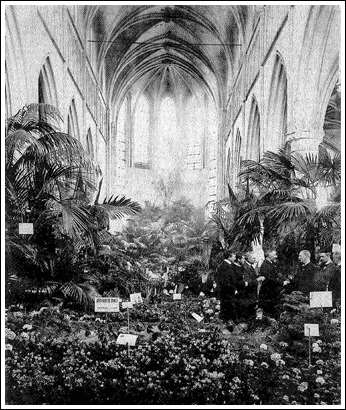

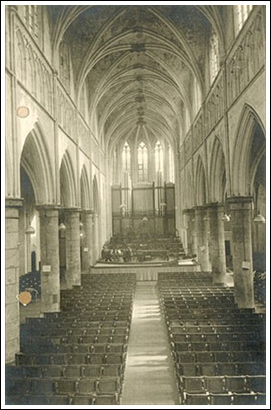

Remmers recently met with a certain Crossroads reporter to answer a few questions about the church, the bookstore, and their shared history. We sat in what was once the sanctuary of the church, and where now buzzes a Coffeelovers café. “You have to mention Coffeelovers,” he insists. “They are a small Maastricht-based coffee store that sells pretty much the best coffee in the world.”

Remmers recently met with a certain Crossroads reporter to answer a few questions about the church, the bookstore, and their shared history. We sat in what was once the sanctuary of the church, and where now buzzes a Coffeelovers café. “You have to mention Coffeelovers,” he insists. “They are a small Maastricht-based coffee store that sells pretty much the best coffee in the world.”